Reading

your mother and mine

The dead don’t know that they’re dead. You’re dead. You’re dead now. Wake up. You’re dead. The living ring the bells. It’s a gentle, far off sound. Wake up. You’re dead.

You slip through the ice and take your two younger siblings with you. You fumble in the cold, dark water, bring them up one by one. Running home across the frozen lake, all of you wet, a kid under each arm, each of you much too cold, your clothes heavy with winter lake water. Your mother kisses you. She’s warm and soft. She says, “I didn’t know you were such a good swimmer.” You are only ten years old.

When I was eight, my mother was in the kitchen making dinner and I was wanting something, I don’t remember what, but I was frustrated and angry. I threatened to kill myself. She laughed. Which made me even more angry. I said, “I will. I’ll do it.” I took the butcher knife from the wood block and pointed it at my chest. She was at the stove. She turned. One hand on the counter, the other on her hip. “Go on.”

You are older than I am. You were graduating college when I was being born. While my mother was anesthetized, I was cut from her body.

You were lost in the jumble of siblings.

I was just lost.

I don’t know how many times I ran away from home. But my mother would often help me pack my bag. I remember one time, I left in the darkness, I walked down the driveway and into the night. I usually just stood at the door being held open for me. I’d turn back, go up the stairs, embarrassed, and get into bed and cry. But this time I went all the way out. I walked across the bridge and then down and along the other side of the lake. I stopped near the old rotting row boat. The moon was out but I couldn’t see much. I heard the ducks swimming in the water. It was a soft sound. Soft gliding strokes. Water dripping from their wings. I remember hearing my sisters calling for me. I was sitting with my knees against my chest. My arms wrapped around tight. Hunkering down. I wanted to stay out all night.

Your mother is dying. You want to know how to say goodbye to her, a mother you do not love. I want to know why you do not love a mother who praised you for saving the life of the children you almost killed. How do you not love her? How?

It is said that if you wake up seven times in your dreams, you will have the ability to wake up in your death. I’ve woken in my dreams five times. Five dreams of awareness. Five times I was wide and knowing. All of me awake and aware at the same time.

If I die tomorrow, please, ring the bells for me. Don’t let me get lost again. Tell me that I’m dead. Love me enough to remind me. You’re dead, Nicki, wake up, you’re dead.

Cats Playing with Cats

Imagine

Can you do other things besides read?

With the rain and the cold

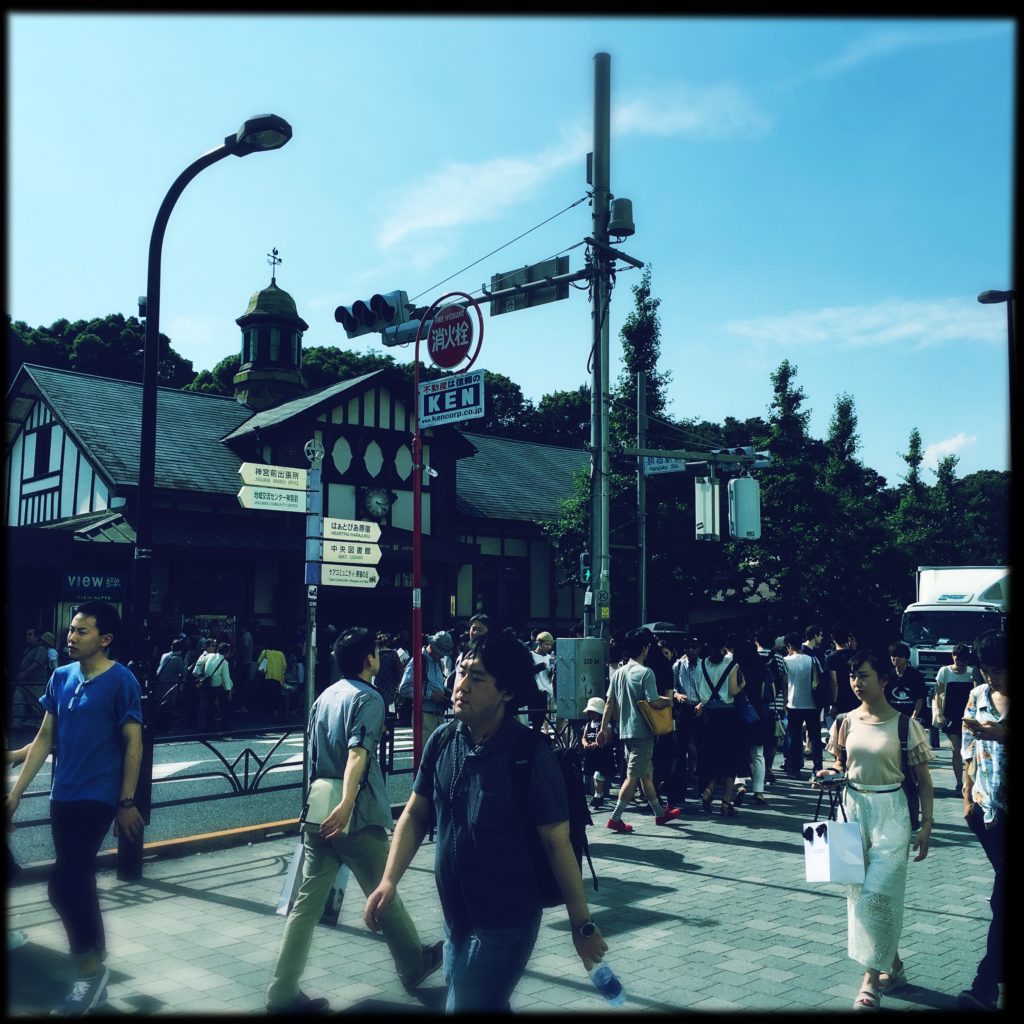

Street

Enchantments

When I was a little kid, we had family come visit from Germany. They stayed for three weeks. My mom was very excited. I was in elementary school but I don’t remember what grade. Maybe second. A lot of things were going on that I was not aware of. Like my mom taking diet pills so that she would look good. I do have an image of her cooking in the kitchen with masking tape over her mouth. But I didn’t understand why. It was so that she wouldn’t absent mindedly taste while she cooked. No extra calories.

Memory is often like piecing together a vague dream.

We took the Germans to Disneyland. Maybe Butterfields. I think the photo above is from Disney’s Frontierland.

We went to family reunions. I remember an older man with exceptionally long fingernails. His name was Sharky.

There was a picnic at a park. The photo below is from that. Someone brought a quilt to share.

And there was Heidi and Sabine staying at our house. They were maybe 18, 19 years old. We took them to our pool and Heidi got a tan while Sabine got a terrible sunburn and had to be inside in the dark for three days, resting on her stomach, to recover. I remember sneaking into her room to check on her and her hardly responding. The room was dark and cool. Her face turned to the wall away from me.

Heidi taught me German. We’d sit across from each other at the dining room table and roll a marble back and forth. At first, she’d say the word in German and Roll the marble to me. I would repeat the word, roll the marble back. Once I knew enough words, the game switched. If she said the word in German, I’d have to say it in English. If she said the word in English, I’d have to say it in German. The marble went back and forth between us. Getting faster and faster. It was fun. The magic of a green marble and words.

I remember Heidi wrote something down for me on a slip of paper and my grandfather asked to see it. I held it out for him to see but it was much too close to his face for him to focus on—I was just a little kid, what did I know? He took it from me and shoved the piece of paper in my face and said, “Can you see that?”

The most German part of my personal history, though, is a song. My great grandmother Mutti sung it to my mother when my mother got hurt, and my mother sung it to us when we got hurt. It involves kissing and chanting. It’s a sort of magical incantation for minor physical wounds. I’ve been trying to figure out the words these days but can’t. My mother no longer sings it correctly so she’s not helpful. And my German is so weak these days that I’m not helpful. It’s Schwaben, so the Internet isn’t helpful either. Every now and then, I look up German folk songs and such but cannot find even a hint of it. In our family the song came to be known as the Cha-Cha. When my first nephew would get injured, he’d come running to whoever, hold out the boo-boo, and say cha-cha. Soon the scrape or bruise would be all better and he’d run off to play again. The magic of rhyme and kisses.